Resource Management: One is not Zero, Part 1

Welcome back to Resource Management, my series examining the various resources available to you as a Magic player and how you can use them. Previously, we’ve looked at card advantage, and how leveraging this can get you ahead in the game. Today, we’re going to look at arguably the most important resource available to you as a player: your life total.

Your life total’s importance is clear, and one of the first things you’ll learn when you start the game is that you cannot let it hit zero. If all your lands are destroyed, you can continue playing. If your whole hand is discarded, the game goes on. If you run out of life, however, you’re out. Dead. There’s no coming back. So you always want to keep your life total high, then? Fortunately for us complexity loving gamers, it’s not quite that straight forward.

Life Management

The life total, like the myriad of other resources available to you, is a tool to be managed. Yes, you don’t want to take damage forever, and yes, you want your opponents’ total to hit zero before yours, but as the old adage goes: one is not zero. Basically, your last point of life is the only one that really matters; the previous nineteen (or thirty-nine, you crazy Commander players) had little to no effect on the actual game state. You can be on one hundred life and still be incredibly far behind, and – as the saying tries to make clear – be on one life and be crushing your opponent.

In the next few sections, I’m going to break down the various ways you can utilise and view your life total just as you would your cards.

Life and Card Advantage

When most players first begin playing Magic, they often view their life total too highly – sacrificing concepts like card advantage to keep their life total up. When your opponent attacks their lone Harrier Naga (vanilla 3/3) into your single Khenra Eternal (vanilla 2/2) on turn 4, you can choose to either take three damage, down to seventeen, or block and sacrifice your Eternal for the good of your health. If you let the Naga hit you, you’ll lose 15% of your starting life total. So you should block, right?

… no, probably not. In this situation, the 2/2 body is likely more valuable than that three life. If you block, the Naga will keep attacking, and you’ll have less stats to potentially block it in future (or even attack back)! What if you can play a 2/3 to block on your next turn? By itself, it’s doing nothing, but teamed up with a 2/2 that Naga is looking less scary. Now for the other extreme – let’s imagine you’re at five life, and your still lonely Khenra Eternal is instead facing up against this guy:

When your opponent sends the Riverwinder at you, you have two options – block, and lose the Eternal to a watery grave, or not block, and… well, die. While I’m as much of a fan of random 2/2s as the next guy, I’m a bigger fan of not dying. It’s pretty clear in this situation you should block. The middle ground is where it gets interesting, and I think a pretty common level up moment for players who understand that both cards and life are resources, but don’t yet realise when to value life higher.

Let’s say you’re in game two versus your blue opponent in Hour of Devastation limited, and game one went very long – you in fact saw your opponent’s whole deck! You know the biggest thing they can threaten you with is that Riverwinder, a 5/5, and that they have several copies of Unquenchable Thirst. The board is as above – their Riverwinder (and a Desert of the Mindful) versus your Eternal. You’re at ten life, so two attacks are lethal. Both of you have no cards in hand. Your opponent is at six life, you have no removal in your deck that can interact with the Riverwinder, and in your deck are three copies of Inferno Jet.

Your opponent draws for the turn then attacks you. Do you block?

These situations present themselves in both limited and constructed on a pretty regular basis. If you block, you’re giving up a card in exchange for five life. If you don’t block, you take five, dropping to five life. Players who get the basics of life management would likely say no, don’t block – the Riverwinder will come crashing in next turn, and you may draw something that changes the attacks; any three power creature would help the Eternal take it down nicely. If you don’t, you can always block the Riverwinder then. However, I’d argue blocking here makes a lot of sense.

As your opponent is at six life, you are in no position to try and trade damage; you would need to draw a chump blocker every turn and the opponent a blank every turn for the rest of the game. If you let the five through, then draw a blank, you cannot attack the opponent back. You must block. Consequently, you are unlikely to be losing an attack by choosing to block this turn.

Since you have several copies of Inferno Jet that win the game immediately, you are looking to maximise your odds to draw them, and that means increasing your number of draw steps. If you opt not to block here – when your plan is to block next turn if you don’t draw something relevant – you are giving the opponent a chance to draw one of their Unquenchable Thirsts, and kill you on the spot. If you do block here, you know you have two extra draws before the Riverwinder finishes you off.

This is one example in which card advantage and life management are concepts at odds with each other. This is often the case, so understanding when to focus on one or the other is a very important skill to learn.

Life Gain and Direct Damage

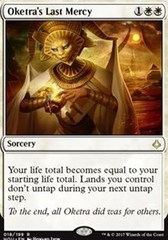

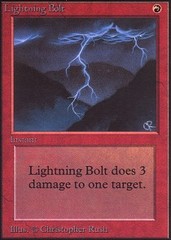

Now, you’ve all probably heard of this card:

Lightning Bolt is as powerful as it is iconic. For a single mana, you get to throw lightning wherever you’d like; Deathrite Shaman? Bzzzt. Jace, the Mind Sculptor? Zap. And when your opponent is hurting and their life is low, you can skip the foreplay, and chuck it right at their head. I’m amped! Bolt is efficient and versatile, doing whatever you need whenever you need it. It would surprise me as much to see it out of Jeskai Control as it would Burn. Now, for its’ awkward cousin:

When your opponent plays a Mountain into a Lava Spike, things are a little less vague. Spike does a fraction of what Bolt can do; killing creatures is Bolts’ bread and butter. What it and Bolt both can do, however? Get your opponent dead.

Direct damage spells are the antithesis of the trade-off of life for card advantage – throwing a bolt at the opponents’ face costs you a card, and costs them nothing. As above, it’s only that last life point that matters, so if you deal anything up to nineteen damage but don’t get that last one, you have wasted a lot of resources doing nothing. However, if you do manage to hit that critical twentieth point, it doesn’t matter how many cards the opponent has. It doesn’t matter what their board looks like. It doesn’t matter how many cards they have in deck, how much mana they have access to, or what sweet spells they’ve cast – they’re dead. Straight face burn is all about virtual card advantage; it doesn’t matter how many more resources they have if they’re out of the most important one.

On the other side of the spectrum, let’s look at some life gain:

New players will often see cards like Feed the Clan and get excited – if you gain lots of life, it’s difficult to lose, right? Well, no. As with my previous article on card advantage and per the above, lots of life does not equal winning.

Imagine a scenario in which you’ve cast four copies of Feed the Clan (with Ferocious), and gained 40 life. You now have triple your starting life total! Unfortunately, while you spent mana and cards to increase this resource, your opponent played creatures, and is attacking you. You’ve got few cards left to affect the board, whether creatures or removal, and still the opponent keeps attacking. Even if the opponent has to take longer to finish you off, your trade of cards for life has only prolonged the inevitable.

Now there are situations in which straight life gain spells can be powerful – if your Feed the Clan gains ten life, and your opponent spent three cards throwing nine damage at you directly, your Clan just traded three for one! These are niche scenarios, however, and easily recognised when they appear. For the most part, your creatures and removal spells are likely to gain you as much or more life (by your creature being on blocks preventing attacks from the opponent, or a removal spell killing an opposing creature that could have attacked you).

Summary

Today, we’ve looked at life as a resource compared to cards – when it can be correct to focus on your life total or your cards. The topic is not cut and dry, and I’m sure there are those who will disagree with my above examples; but that’s the beauty of Magic!

Next week, I’ll be looking at the other side of life total management: buffering and lowering it incidentally, and recognising when you should concede life to the opponent in exchange for information. What do I mean? Join next week and find out.

As always, if you have any questions or ideas, please leave them in the comments below. Good luck!