Resource Management: The 2 for 1, Part 2

Welcome back to Resource Management, my series examining the various resources available to you as a Magic player and how you can use them. Last week, we began with our look at cards as a resource, focusing specifically on raw card advantage – for the uninitiated, the link to that article follows: http://articles.trolltradercards.com/2017/07/26/resource-management-the-2-for-1-part-1/

In brief, raw card advantage is the concept of having more total cards available to you than your opponent, and looking at how you may generate these extra cards. However, there’s a lot more to Magic than that – as much as many of us would like it to be the case, you don’t automatically win when you draw ten more cards than your opponent! This week, we’re going to look at virtual card advantage.

Virtual Card Advantage

Raw card advantage is a simplistic way of viewing card advantage, as it assumes that all cards are created equally – if you have ten cards and your opponent has just one, you must be winning, right? While this is likely to be true, it’s not always the case!

Virtual card advantage goes a level deeper, looking less at the number of cards you have and more on what each card is doing. If raw card advantage is all about quantity, virtual card advantage is about quality. Today we’re going to look at the ways cards can be valued, how those values can change, and what you can do to generate virtual card advantage.

Relevance

Picture this scenario: your opponent puts a Tarmogoyf onto the stack, with no cards in hand, and nothing else on board. Your last card in hand is a good one, though – you let the Goyf resolve, and during your opponents’ end step, you cast a huge Sphinx’s Revelation for X equals 7, drawing an entirely new hand! Thinking there’s no way you can lose, you untap, draw for your turn, and look at your eight fresh cards:

Eight lands! You’re now up eight cards in hand on your opponent, but you can’t do anything! This is an extreme example of virtual card advantage in action – you may be technically up in card advantage, but your cards are not relevant. For practical purposes, that Revelation did nothing but gain you seven life. Now, instead, let’s imagine that you still drew eight lands, but amongst them were two copies of the following:

Now we’re talking. You’d much rather have drawn a few spells, but at this late stage of the game when you have access to ten or more mana, Colonade does a pretty good impression of Serra Angel – and two of them is no joke. That Goyf is looking much less impressive now! Colonade is a relevant card in this situation.

Drawing lands when you need spells is an obvious form of cards not being relevant; I’m sure we’ve all had that moment where we’re praying for a nonland on top of our libraries. However, there are other situations that make certain spells irrelevant:

With your opponent at zero cards in hand, the Bridge effectively makes all your creatures irrelevant – for decks that rely on creatures to win, this is a pretty big issue! The Lantern Control deck pioneered by Zak Elsik was designed entirely with this concept in mind. By playing cards like the Bridge to make creatures irrelevant and controlling their opponents’ draws with various mill effects and Lantern of Insight, the deck can ensure the few relevant spells left in your deck do not find their way to your hand!

Shapeshifting

While there are many situations than can change the value of cards, there are more direct ways of changing them:

Song of the Dryads is a great example of virtual versus raw card advantage. Let’s say you enchant your opponent’s Elspeth, Sun’s Champion with Song. From a raw card advantage standpoint, you’re actually down a card in this transaction – you have put a card into play, but it has had no effect on the game. Your opponent’s Elspeth is still there… but this approach wildly ignores that she will be doing her best impression of a tree! From a technical standpoint, you are down a card, but practically and intuitively, their Elspeth has been taken out. This situation assumes that the extra mana she will now provide is not important, but which would you rather face – an extra land, or one of the most powerful planeswalkers ever printed?

In a similar vein, let’s look at another green shapeshifter:

Nissa likes lands. A lot. She likes them so much, in fact, that she’s happy to raise them up and start fighting alongside them. Much like Song, Nissa alters the types on a card, but she does the reverse – she improves your lands by adding a card type, an ability, and power/toughness. Again, this does not technically generate raw card advantage, but practically speaking she is drawing and casting a zero mana 4/4 with trample (and usually haste) every turn. By the time she is joining the battle, your lands are likely to have lost much of their value as you’ve already cast most of your spells, and you’d trade them away for more creatures in a heartbeat.

Finally, a look at a slightly less direct change of resources:

Path lets you get rid of any creature for a single mana at instant speed, no questions asked. But it comes at a cost: your opponent getting a land instead. Ignoring for a moment the occasions when your opponent cannot fetch a land – not an uncommon occurrence against basic land-light decks in Modern – how good is this ability? Ultimately, you’re losing a card and your opponent replaces theirs with a new card. That’s a two for one in your opponents’ favour, and unlike Song, you can’t deal with any permanent, only creatures. The key to the strength of Path is the understanding that all cards are not equal.

Let’s say your opponent is on an aggressive red deck, and after you’ve played your land on turn 1, they start with a turn 1 Goblin Guide – a powerful play. After it’s attacked, you have a choice: you can play the Path, or you can save it for a future target and take the two damage.

While you would prefer an unconditional removal spell in this situation i.e. Fatal Push, it can be correct to cast the Path anyway. If you commit to destroying a future target, the Goblin could easily deal four or even more damage to you, and against a deck packing a lot of burn, that damage adds up quickly! Even worse is if you decide to cast your Path in a turn or two on the Goblin, as recouping the lost mana and life will be hard to do. The flipside of this is that you are ramping your opponents’ mana, allowing them to cast their spells more quickly – however, an aggressive deck will generally not have much need for lands beyond the third or fourth, so after a turn or two, that extra land is likely to become irrelevant. Further, this is turn one, the worst time for Path – flash forward to turn four or later, and that extra land is likely to do nothing.

But what if the opponent is colour screwed, and killing their guy opens up their hand? Or if they’re one mana short of casting their deck’s key card, and have been stuck on mana a few turns? I did say virtual card advantage was deep!

Prison

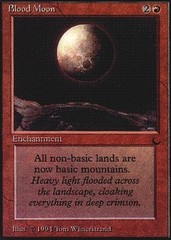

When talking about virtual card advantage, prison effects often come to mind. These are traditionally effects that stop your opponent from taking an action, often by denying them of a resource such as mana. An infamous example:

Blood Moon does not seem flashy on the face of it. It costs three mana, does not affect the board when it resolves, and is in fact technical card disadvantage – you spent a card to do nothing. But that’s just what prison effects do – nothing.

Against non-red opponents, Blood Moon effectively turns all opposing dual lands into colourless lands. Against three or more colour decks, which often only play a handful of basics, this can be devastating. For a moment, let’s picture an opponent with zero basic lands. Blood Moon may not have directly destroyed or discarded any cards, but by its presence preventing your opponent from casting spells, it has practically traded for their entire deck. A sixty for one!

Now, you’re unlikely to play against a deck that has zero basics – as Path and Moon show, you will often need basics not just for your own deck but also to weaken opposing cards – but another example of this effect doesn’t care how much mana you have:

Iona is flashy. ‘Your opponents can’t cast spells’ is a very uncommon line of text in Magic, and for good reason. When Iona hits the board against a mono-coloured opponent and names their lone colour, she has destroyed every card in the opposing hand and library; she just does it with more flair than Moon.

Prison effects are also not relegated to just mana denial – another commonly seen card is widely considered one of the best sideboard options in Modern:

Against decks with numerous artifacts, Stony can be crippling. No more artifact mana, no more creature abilities, no more equipment; Modern Affinity, for example, gets totally shut down. Prison effects are quite clean examples of virtual card advantage, as they very obviously change a card’s value to near or total worthlessness. Seven worthless cards do not beat one good one!

Blanking

Lastly concerning virtual card advantage is the concept of blanking. If cards being irrelevant is passive i.e. you cannot control having drawn too many lands, blanking cards is active; making cards become irrelevant. There are many ways to do this, so let me break it down with a scenario.

You’re playing HOU limited, and your opponent has two Defiant Khenra in play: two 2/2s with no text. You cast a Harrier Naga, a 3/3 with no text. Without any outside assistance interfering such as removal or pump spells, your opponents’ Khenra cannot profitably attack, as you would allow one through and block the other. Essentially, your opponent would trade two damage for one Khenra. As long as life totals are relatively high, this is generally a highly unfavourable trade for the opponent.

Conversely, if your opponent leaves both Khenra untapped, your Naga cannot profitably attack – if you do, your opponent can double block with both, and your 3/3 would trade for a 2/2. This is certainly a better result than the possible attack your opponent could make, but you would generally rather not trade a better creature for a worse one. Consequently, in most circumstances, your Naga will not attack and neither will their Khenra. As neither player is attacking, neither player is blocking, and so all three creatures sit in play idly staring at each other. Casting your Naga has made both of your opponents’ Khenra into blanks, and at the same time, they have made your Naga into a blank.

Effectively, your Naga became a removal spell that killed two 2/2 creatures. Now, this is not exactly the same thing – if the opponent untaps and kills your Naga, the work it did is immediately undone – but if the board stays as is, you have scored a virtual two for one.

Let’s take this one step further – it’s the same game but a few turns later. Your opponent is holding an Open Fire for your Naga, but waiting for the right time to cast it and enable a good attack. Unfortunately for them, they tapped out to play a spell, and you cast a Cartouche of Strength. Disaster! Now, not only has one of their creatures in play been binned, but their Open Fire does not kill the Naga alone anymore. Your Cartouche has managed to virtually trade two for one with a creature and their removal spell.

These are common examples of blanking that occur in both limited and constructed, but another occurrence you’ll see particularly in constructed are removal spells vs. creature-light decks. Archetypical Control will often play few to no creatures, focusing on one or two powerful threats to end the game by themselves. This is mainly so they can focus on playing more answers and card draw, but as a side effect, it makes these cards in the opponents deck quite a bit worse:

While the effectiveness of these spells does depend on the construction of the opposing deck, generally, these are total blanks versus Control. Even if the opposing deck does have targets, by the time they appear, the Control deck has reached its late game and achieved its goal; they can even counter the removal spells if they choose!

As you can see, blanking cards is a very powerful technique that you should aim for whenever possible, both in play and during deck construction. Look at the context of a format – are there lots of four damage removal spells? Play X/5s. Lots of ground creatures? Play fliers. Lots of artifact removal? Avoid artifacts.

Summary

In my last article, we espoused the benefits of drawing lots of cards. While there was a lot to take away, I hope that this one has made it clear – the quantity of cards you have is important, but the quality is just as if not more important. Raw and virtual card advantage: if you can take both of these ideas to heart, you’ll know which cards have what value at various points in the game, and be poised to take your opponents down.

Thanks for reading the first part of this series on Resource Management – next up, we’ll be covering the life total. If you have any questions or ideas, please leave them in the comments below. Good luck!